During my master’s program at Bowling Green State University, where I studied College Student Personnel — a field preparing individuals to support student development in higher education settings — one foundational course required for all master’s students focused on psycho-social development models. This course aimed to equip us with the knowledge needed to support the future students with whom we would work.

The course covered theories such as self-identity development, intellectual and ethical development, moral development, social-identity development (e.g., racial, ethnic, gender, sexuality, and faith identity development), and many others. Among the theories covered, it was King and Kitchener’s Developing Reflective Judgment model that left a lasting impact on my approach to social justice and my work as a diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) practitioner in higher education.

Reflective judgment is a cognitive development model consisting of seven stages that describe how assumptions about knowledge and concepts of justification develop from adolescence to adulthood. Reflective judgments are made by examining and evaluating relevant information, opinion, and available explanations (the process of reflective thinking), then constructing plausible solutions for the problem at hand, acknowledging that the solution itself is open to further evaluation and scrutiny.

This model differs from critical thinking by focusing on ill-structured problems, such as those related to social justice. Understanding reflective judgment is crucial when addressing such issues, as it provides a framework for evaluating and constructing solutions. The King & Kitchener Reflective Judgment Model (1994) includes three main stages.

Pre-Reflective Thinking (Stages 1, 2, and 3)

- Stage 1: Views knowledge as absolute and concrete, obtained with certainty through direct observation. Different beliefs are not acknowledged.

- Stage 2: Assumes knowledge is certain but not immediately available, relying on authority figures without critical thinking.

- Stage 3: Acknowledges temporary uncertainty in knowledge, with personal beliefs valid until absolute knowledge is obtained.

Quasi-Reflective Thinking (Stages 4 and 5)

- Stage 4: Acknowledges uncertainty in knowledge, influenced by situational variables and involving ambiguity.

- Stage 5: Views knowledge as contextual and subjective, filtered through personal perceptions and criteria for judgment.

Reflective Thinking (Stages 6 and 7)

- Stage 6: Constructs individual conclusions about ill-structured problems based on evaluations of evidence and opinions from reputable sources.

- Stage 7: Recognizes knowledge as the outcome of a reasonable inquiry, continually reevaluated based on new evidence.

While the King & Kitchener model is a stage model, individuals can occupy two to three adjacent stages simultaneously, and their stage can change based on the challenges they face.

It is essential to also note how this model and theory are rooted in western colonial ideas of knowledge and ‘knowing.’ Western science sees knowledge as a product of academic and literate transmission, using empirical data to form conclusions about trends within a problem. In Western societies, we hold up published peer-reviewed journal articles as the authority on knowledge.

Traditional knowledge systems, however, adopt a more holistic approach, and do not separate observations into different disciplines as does Western science. Moreover, traditional knowledge systems do not interpret reality on the basis of a linear conception of cause and effect, but rather as a world made up of constantly forming multidimensional cycles in which all elements are part of an entangled and complex web of interactions.

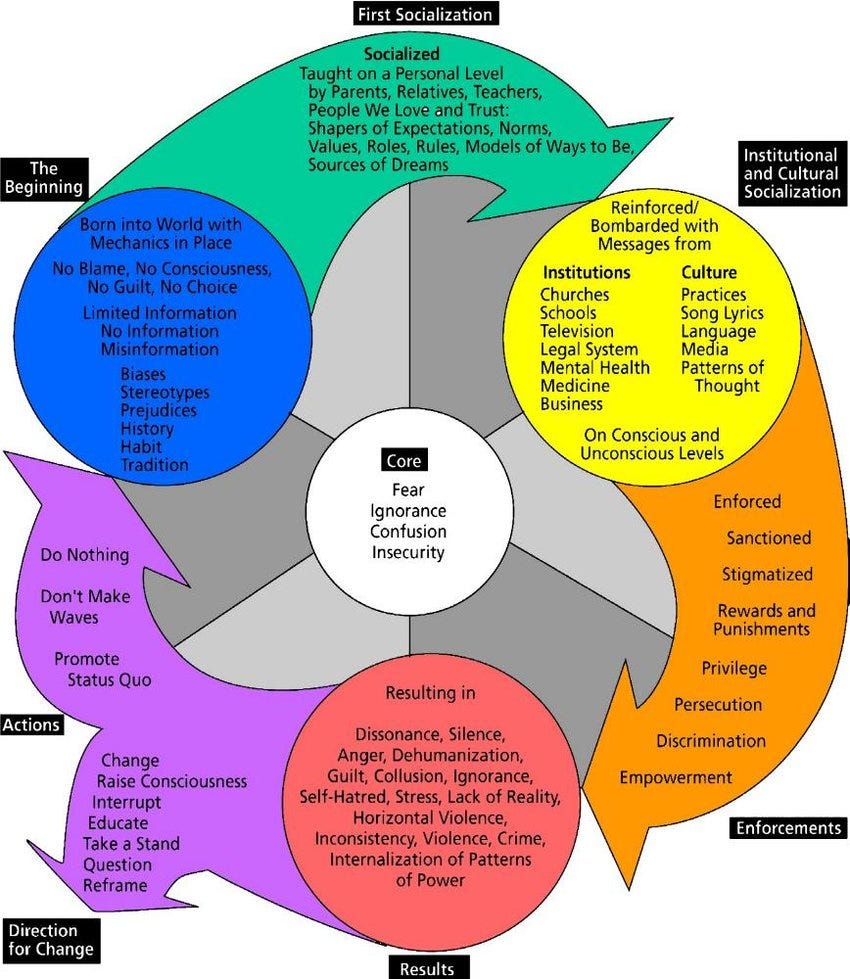

The Cycle of Socialization

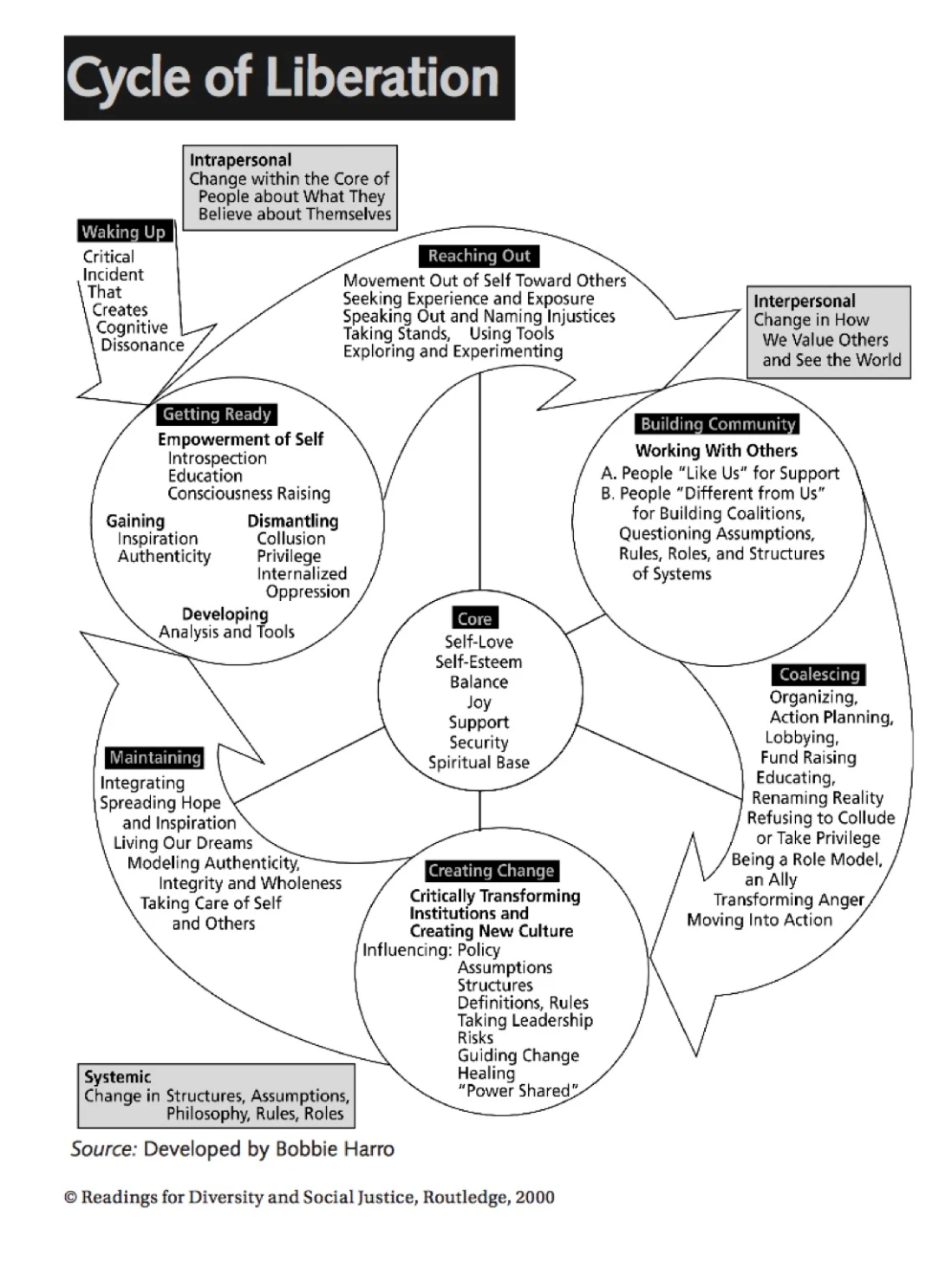

Bobbie Harro’s Cycle of Socialization explains how individuals are socialized within established systems of power and privilege, impacting their worldview. Encountering critical incidents, or perturbations, disrupts this cycle, leading to cognitive growth.

Swiss psychologist, Jean Piaget, “emphasizes that cognitive growth is the result of perturbations within existing schemes…”. Critical incidents challenge individuals to reflect on and modify their views, initiating “waking up” in the Cycle of Liberation, according to Harro.

To foster extensive cognitive growth, individuals must encounter a high density of perturbations or critical incidents (e.g., three to four a day). Reflective thinking is crucial for navigating diverse perspectives and challenging biases. Most people grow up in homogenous communities, requiring intentional efforts to step out of these circles and encounter critical incidents.

Ask yourself “how many of your close friends are of a different race, different religion, different ethnicity or culture, different family background, different socioeconomic status, different gender, different sexuality?” Then ask yourself, “how much do you know and discuss with these friends their lived experiences and realities?”

Reflective Judgment and DEI

King & Kitchener found that college students typically start in stages three or four, progressing to stage four by senior year. Liberto et al. (1990) found that rural American high school graduates with no higher education experience, on average, were in stage two of the model, relying mostly on their conservative religious beliefs to guide their knowledge about reality. Reflective Judgment’s relevance is evident in DEI work, where disrupting the cycle of socialization can be challenging.

DEI practitioners face difficulty disrupting socialization cycles during one-off trainings or workshops due to these being low density critical incidents for most. Many attendees resist DEI training for various reasons, hindering their move to reflective thinking stages. Critiques on DEI and methodologies like critical race theory further complicate creating inclusive spaces in higher education, which makes it more difficult to make these spaces safe for diversification.

Understanding reflective judgment and its stages is crucial for navigating ill-structured problems, particularly in DEI work. The challenges of disrupting socialization cycles underscore the crucial need for intentional efforts to expose individuals to diverse perspectives and critical incidents, fostering cognitive growth and reflective thinking.